Home

Bibliography

Contact

Interesting Articles

Given its liquid and vital status, cash is typically listed first within the current asset section of the balance sheet. But what exactly is cash? Obviously, cash includes coins and currency. But what about items like money on deposit in bank accounts, undeposited checks from customers, certificates of deposit, and similar items? Some of these are deemed to be cash and some are not. What rule shall be followed?

Generalizing, cash includes those items that are acceptable to a bank for deposit and are free from restrictions (i.e., available for use in satisfying current debts). Cash typically includes coins, currency, funds on deposit with a bank, checks, and money orders. Items like postdated checks, certificates of deposit, IOUs, stamps, and travel advances are typically not classified as cash. The existence of compensating balances (amounts that must be left on deposit and cannot be withdrawn) should be disclosed; if such amounts are very significant, they are reported separately from cash. Also receiving separate treatment are "sinking funds" (monies that must be set aside to satisfy debts) and heavily restricted foreign currency holdings (that cannot easily be converted into dollars). These unique categories of funds may be reported in the long-term investments category.

CASH EQUIVALENTS

Cash equivalents arise when companies place their cash in very short-term interest-earning financial instruments that are deemed to be highly secure and will convert back into cash within 90 days. Many short-term government-issued securities (e.g., treasury bills) meet these conditions. In addition, active markets exist for such securities, and these financial instruments are usually very marketable in the event the company needs access to funds in advance of maturity. Cash management strategies dictate that large amounts of cash not be held in "unproductive" accounts that do not generate interest income. As a result, surplus cash is often invested in these instruments. Because of their unique nature, they are considered to be cash equivalents, and are often reported with cash on the balance sheet.

CASH MANAGEMENT

It is very important to ensure that sufficient cash is available to meet obligations and to make sure that idle cash is appropriately invested to maximize the return to the company. One function of the company "treasurer" is to examine the cash flows of the business, and pinpoint anticipated periods of excess or deficit cash flows. A detailed cash budget is often maintained, and updated on a regular basis. The cash budget is a major component of a cash planning system and represents the overall plan of activity that depicts cash inflows and outflows for a stated period of time. A future chapter provides an in-depth look at cash budgeting.

You may tend to associate cash shortages as a sign of weakness, and, indeed, that may be true. However, such is not always the case. A very successful company with a great product or service may be rapidly expanding via new business locations, added inventory levels, growing receivables, and so forth. All of these events give rise to the need for cash and can create a real crunch even though the business is fundamentally prospering. To sustain the growth, careful planning must occur.

STRATEGIES TO ENHANCE CASH FLOWS: As a business looks to improve cash management or add to the available cash supply, a number of options are available. Some of these solutions are "external" and some are "internal" in nature.

External solutions include:

Issuing additional shares of stock -- This solution has a definite advantage, because it allows the company to obtain cash, without a fixed obligation to repay. As a result, this may seem like a sure-fire costless option. Unfortunately, the existing shareholders do incur a very real detriment, because the added share count dilutes their ownership proportions. In essence, it is akin to existing shareholders selling off part of the business; a solution that may be seen as a last resort if the future is bright.

Borrowing additional funds -- This solution brings no additional shareholders to the table, but borrowed funds must be repaid along with interest. Thus, the business cost and risk is increased. On a related note, many companies will establish a standing line of credit that enables them to borrow as needed, and not borrow at all if funds are not needed. This solution provides a ready source of liquidity, without actually increasing debt levels. Banks typically provide such lines of credit in exchange for a fee based on the amount of the line of credit.

The company may look within its own operating structure to find internal cash flow enhancements:

Accelerate cash collections -- If a company can move its customer base to pay more quickly, a significant source of cash is found! Simple tools include electronic payment, credit cards, lockbox systems (i.e., the establishment of bank depositories near to the customer for quick access to funds/thereby avoiding mail and clearing delays), and cash discounts for prompt payment.

Postponement of cash outflows -- Companies may "drag their feet" on cash outflows, delaying payment as long as possible. In addition, paying via check sent through the mail allows use of the "float" to preserve cash on hand. However, you need to know that it is illegal to issue a check when there are insufficient funds in the bank to cover that item (even if you know a deposit is forthcoming that will cover the check). Some companies make travel advances to employees for anticipated costs to be incurred on an upcoming trip; it is better for cash flow to have the employee incur the cost (perhaps on a credit card) and then submit receipts for reimbursement.

Cash control -- Systems and procedures should be adopted to safeguard an organization's funds. Internal control for cash is based on the same general control features introduced in the previous chapter; access to cash should be limited to a few authorized personnel, incompatible duties should be separated, and accountability features (like prenumbered checks, etc.) should be developed.

- The control of receipts from cash sales should begin at the point of sale and continue through to deposit at the bank. Specifically, cash registers (or other point-of-sale terminals) should be used, actual cash on hand at the end of the day should be compared to register tapes, and daily bank deposits should be made. Any cash shortages or excesses should be identified and recorded in a Cash Short & Over account.

- Control of receipts from customers on account begins when payments are received (in the mail or otherwise). The person opening the mail should prepare a listing of checks received and forward the list to the accounting department. The checks are forwarded to a cashier who prepares a daily bank deposit. The accounting department enters the information from the listing of checks into the accounting records and compares the listing to a copy of the deposit slip prepared by the cashier.

- The controls over cash disbursements include procedures that allow only authorized payments for actual expenditures and maintenance of proper separation of duties. Control features include requiring that significant disbursements be made by check, performance of periodic bank reconciliations, proper utilization of petty cash systems, and verification of supporting documentation before disbursing funds.

BANK RECONCILIATION

One of the most common cash control procedures, and one which you may already be performing on your own checking account, is the bank reconciliation. In business, every bank statement should be promptly reconciled by a person not otherwise involved in the cash receipts and disbursements functions. The reconciliation is needed to identify errors, irregularities, and adjustments for the Cash account. Having an independent person prepare the reconciliation helps establish separation of duties and deters fraud by requiring collusion for unauthorized actions.

There are many different formats for the reconciliation process, but they all accomplish the same objective. The reconciliation compares the amount of cash shown on the monthly bank statement (the document received from a bank which summarizes deposits and other credits, and checks and other debits) with the amount of cash reported in the general ledger. These two balances will frequently differ. Differences are caused by items reflected on company records but not yet recorded by the bank; examples include deposits in transit (a receipt entered on company records but not processed by the bank) and outstanding checks (checks written which have not cleared the bank). Other differences relate to items noted on the bank statement but not recorded by the company; examples include nonsufficient funds (NSF) checks ("hot" checks previously deposited but which have been returned for nonpayment), bank service charges, notes receivable (like an account receivable, but more "formalized") collected by the bank on behalf of a company, and interest earnings.

The following format is typical of one used in the reconciliation process. Note that the balance per the bank statement is reconciled to the "correct" amount of cash; likewise, the balance per company records is reconciled to the "correct" amount. These amounts must agree. Once the correct adjusted cash balance is satisfactorily calculated, journal entries must be prepared for all items identified in the reconciliation of the ending balance per company records to the correct cash balance. These entries serve to record the transactions and events which impact cash but have not been previously journalized (e.g., NSF checks, bank service charges, interest income, and so on).

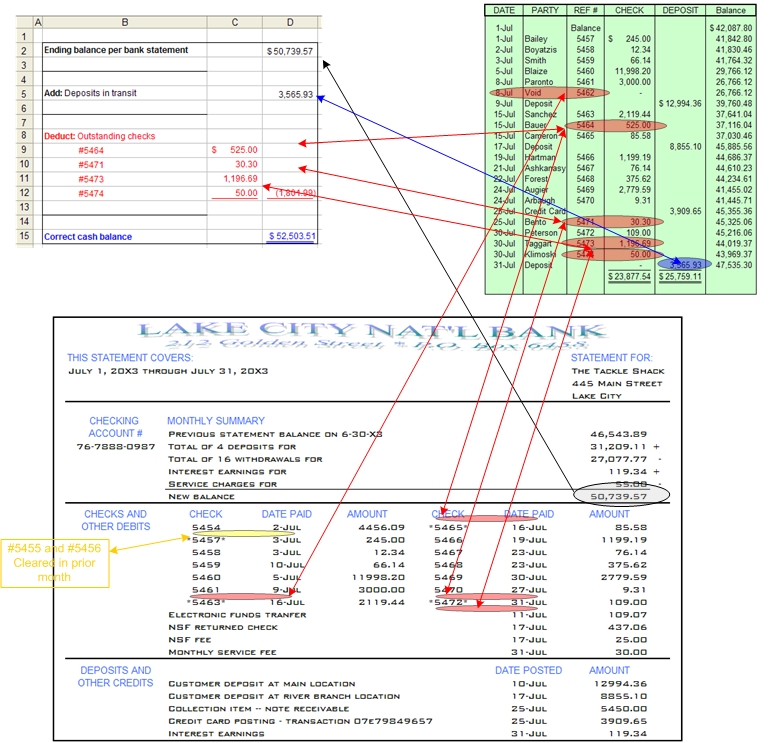

The above bank statement is for The Tackle Shop for July of 20X3. The following additional data is needed to reconcile the account:

- The first check listed above, #5454, was written in June but did not clear the bank until July 2.

- There were no other outstanding checks, and no deposits in transit at the end of June.

- The EFT (electronic funds transfer) on July 11 relates to the monthly utility bill; The Tackle Shop has authorized the utility to draft their account directly each month.

- The Tackle Shop is optimistic that they will recover the full amount, including the service charge, on the NSF check ("hot check") that was given to them by a customer during the month.

- The bank collected a $5,000 note for The Tackle Shop, plus 9% interest ($5,450).

- The Tackle Shop's credit card clearing company remitted funds on July 25; the Tackle Shop received an email notification of this posting and simultaneously journalized this cash receipt in the accounting records.

- The Tackle Shop made the 2 deposits listed above, and an additional deposit of $3,565.93 late in the afternoon on July 31, 20X3.

- The ending cash balance, per the company general ledger, was $47,535.30.

- The following check register is maintained by The Tackle Shop, and it corresponds to the amounts within the Cash account in the general ledger:

The bank reconciliation for July is determined by reference to the above bank statement and other data. You must carefully study all of the above data to identify deposits in transit, outstanding checks, and so forth. Be advised that tracking down all of the reconciling items can be a rather tedious, sometimes frustrating, task. Modern bank statements facilitate this process by providing sorted lists with asterisks beside the check numbers that appear to have gaps in their sequence numbering. Below is the reconciliation of the balance per bank statement to the correct cash balance. You should try to identify each item in this reconciliation within the previously presented data.

Even this fairly simple bank reconciliation demonstrates the pressing need for monthly reconciliations. Without a reconciliation, company records would soon become unreliable as the process draws attention to various needed adjustments.

PETTY CASH

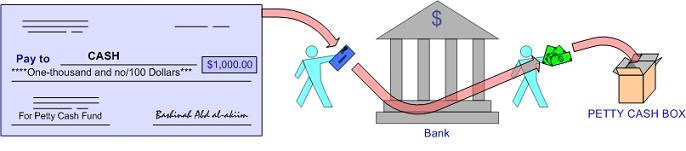

Petty cash, also known as imprest cash, is a fund

established for making small payments that are impractical to pay by

check. Examples include postage due, reimbursement to employees for

small purchases of office supplies, and numerous similar

items.

The establishment of a petty cash system begins by making out a check

to cash, cashing it, and placing the cash in a petty cash box:

A petty cash custodian

should be designated to have responsibility for safeguarding and making

payments from this fund. At the time the fund is established,

the

following journal entry is needed. This journal entry, in

essence, subdivides the petty cash portion of available funds into a

separate account.

| 1-31-X4 |

Petty Cash |

1,000 |

||

|

Cash |

1,000 |

|||

| To establish a $1,000 petty cash fund |

REPLENISHMENT OF PETTY CASH: As expenditures occur, cash in the box will be depleted. Eventually the fund will require replenishment back to its original level. To replenish the fund, a check for cash is prepared in an amount to bring the fund back up to the desired balance. The check is cashed and the proceeds are placed in the petty cash box. At the same time, receipts are removed from the petty cash box and formally recorded as expenses.

The journal entry for this action involves debits to appropriate expense accounts as represented by the receipts, and a credit to Cash for the amount of the replenishment. Notice that the Petty Cash account is not impacted -- it was originally established as a base amount and its balance has not been changed by virtue of this activity.

| 2-28-X4 |

Supplies Expense |

390 |

||

|

Fuel Expense |

155 |

|||

|

Miscellaneous Expense |

70 |

|||

|

Cash |

615 |

|||

| To replenish petty cash; receipts on hand of $615 -- office supplies ($390), gasoline ($155), coffee and drinks ($70). Remaining cash in the fund was $385, bringing the total to $1,000 ($615 + $385). |

CASH SHORT AND OVER: Occasionally, errors

will

occur, and the petty

cash fund will be out of balance. In other words, the sum of

the

cash

and receipts differs from the correct Petty Cash balance.

This

might

be the result of simple mistakes, such as math errors in making change,

or perhaps someone failed to provide a receipt for an appropriate

expenditure. Whatever the cause, the available cash must be

brought

back to the appropriate level. The journal entry to record

full

replenishment may require an additional debit (for shortages) or credit

(for overages) to Cash Short (Over). In the following entry,

$635

is

placed back into the fund, even though receipts amount to only

$615.

The difference is debited to Cash Short (Over):

| 2-28-X4 |

Supplies Expense |

390 |

||

|

Fuel Expense |

155 |

|||

|

Miscellaneous Expense |

70 |

|||

|

Cash Short (Over) |

20 |

|||

|

Cash |

635 |

|||

| To replenish petty cash; receipts on hand of $615 -- office supplies ($390), gasoline ($155), coffee and drinks ($70). Remaining cash in the fund was $365, bringing the total to $980 ($615 + $365; a $20 shortage was noted and replenished. |

INCREASING THE BASE FUND: As a company grows, it may find a need to increase the base size of its petty cash fund. The entry to increase the fund would be identical to the first entry illustrated above; that is, the amount added to the base amount of the fund would be debited to Petty Cash and credited to Cash. Otherwise, take note that the only entry to the Petty Cash account occurred when the fund was established -- subsequent reimbursements of the fund did not change the Petty Cash account balance.

TRADING SECURITIES

From time to time a business may invest cash in stocks of other corporations. Or, a company may buy other types of corporate or government securities. Accounting rules for such investments depend on the "intent" of the investment. If these investments were acquired for long-term purposes, or perhaps to establish some form of control over another entity, the investments are classified as noncurrent assets. The accounting rules for those types of investments are covered in subsequent chapters. But, when the investments are acquired with the simple intent of generating profits by reselling the investment in the very near future, such investments are classified as current assets (following cash on the balance sheet). These investments are appropriately known as "trading securities."

Trading securities are initially recorded at cost (including brokerage fees). However, the value of these readily marketable items may fluctuate rapidly. Subsequent to initial acquisition, trading securities are to be reported at their fair value. The fluctuation in value is reported in the income statement as the value changes. This approach is often called "mark-to-market" or "fair value" accounting. Fair value is defined as the price that would be received from the sale of an asset in an orderly transaction between market participants.

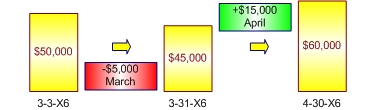

AN ILLUSTRATION: Assume that Webster Company's management was seeing a pickup in their business activity, and believed that a similar uptick was occurring for its competitors as well. One of its competitors, Merriam Corporation, was a public company, and its stock was trading at $10 per share. Webster had excess cash earning very low rates of interest, and decided to invest in Merriam -- intending to sell the investment in the very near future for a quick profit. The following entry was needed on March 3, 20X6, the day Webster bought stock of Merriam:

| 3-3-X6 |

Trading Securities |

50,000 |

||

|

Cash |

50,000 |

|||

| To record the purchase of 5,000 shares of Merriam stock at $10 per share |

Next, assume that financial statements were being prepared on March 31. Despite Webster's plans for a quick profit, the stock declined to $9 per share by March 31. Webster still believes in the future of this investment, and is holding all 5,000 shares. But, accounting rules require that the investment "be written down" to current value, with a corresponding charge against income. The charge against income is recorded in an account called Unrealized Loss on Investments:

| 3-31-X6 |

Unrealized Loss on Investments |

5,000 |

||

|

Trading Securities |

5,000 |

|||

| To record a $1 per share decrease in the value of 5,000 shares of Merriam stock |

Notice that the loss is characterized as

"unrealized."

This term is used to describe an event that is being recorded

("recognized") in the financial statements, even though the final cash

consequence has not yet been determined. Hence, the term

"unrealized."

April had the intended effect, and the stock of Merriam bounced up $3

per share to $12. Still Webster decided to hang on for

more. At the end of April, another entry is needed if

financial

statements are again being prepared:

| 4-30-X6 |

Trading Securities |

15,000 |

||

|

Unrealized Gain on Investments |

15,000 |

|||

| To record a $3 per share increase in the value of 5,000 shares of Merriam stock |

The preceding illustration assumed a single investment. However, the treatment would be the same even if the trading securities consisted of a portfolio of many investments. That is, each and every investment would be adjusted to fair value.

RATIONALE FOR FAIR VALUE ACCOUNTING: The fair value approach is in stark contrast to the historical cost approach used for other assets like land, buildings, and equipment. The rationale is that the market value for trading securities is readily determinable, and the periodic fluctuations have a definite economic impact that should be reported. Given the intent to dispose of the investments in the near future, the belief is that the changes in value likely have a corresponding effect on the ultimate cash flows of the company. As a result, the accounting rules recognize those changes as they happen.

ALTERNATIVE: A VALUATION ADJUSTMENTS ACCOUNT: As an alternative to directly adjusting the Trading Securities account, some companies may maintain a separate Valuation Adjustments account that is added to or subtracted from the Trading Securities account. The results are the same; the reason for using the alternative approach is to provide additional information that may be needed for more complex accounting and tax purposes. One such purpose is to determine the "taxable gain or loss" on sale. Tax rules generally require comparing the sales price to the original cost (you may be surprised to learn that tax rules sometimes differ from accounting rules -- the mark-to-market approach used for accounting is normally not acceptable for tax purposes). There are also more involved accounting rules relating to measurement of the "realized" gains and losses when the securities are in fact sold. Those rules are ordinarily the subject of more advanced courses.

DIVIDENDS AND INTEREST: Since trading securities are turned over rather quickly, the amount of interest and dividends received on those investments is probably not very significant. However, any dividends or interest received on trading securities is reported as income and included in the income statement:

| 9-15-X5 |

Cash |

75 |

||

|

Dividend Income |

75 |

|||

| To record receipt of dividend on trading security investment |

The presence or absence of dividends or interest on trading securities does not change the basic mark-to-market valuation for the Trading Securities account.

DERIVATIVES: Beyond the rather straight-forward investments in trading securities are an endless array of more exotic investment options. Among these are commodity futures, interest rate swap agreements, options related agreements, and so on. These investments are generally referred to as derivatives, because their value is based upon or derived from something else (e.g., a cotton futures contract takes its value from cotton, etc.). The underlying accounting approach follows that for trading securities. That is, such instruments are initially measured at fair value, and changes in fair value are recorded in income as they happen.